|

Parent Article: Immigrant Worker Freedom Rides Rally -- Monday At 7p.m. |

|

Immigrants Travel To Washington To Rally For Broadened Rights |

by Steven Greenhouse

(No verified email address) |

Current rating: 0

28 Sep 2003

|

|

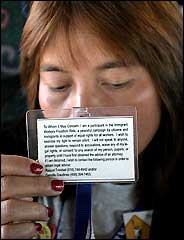

[Photo by Christ Chavez for The New York Times]

Maggie Larson, who flew from Hawaii to Los Angeles to join the freedom ride, remained silent after a border patrol agent asked for her identification documents in Sierra Blanca, Tex.

EL PASO, Sept. 26 — As the bus sped through the New Mexico desert and into West Texas, Federico González talked of his dream, an odd dream for an immigrant from Colombia. He wants to be an F.B.I. agent.

Back home, he had been studying to be a police investigator, but he dropped out of college because he was too poor to pay all the expenses.

Eager to support his girlfriend and infant son, he moved to Arizona and took a job as a roofer, attracted to the relatively high pay by immigrant standards: $9.50 an hour. But the work was grueling, 10-hour days in 100-degree heat. He soon learned there could be a price for protesting harsh conditions.

"They tell me this is the country of freedom," said Mr. González, a passenger in the Immigrant Workers Freedom Ride, a caravan of buses heading to Washington from 10 cities nationwide to campaign for immigrants' rights. "You're supposed to have the right to speak. But immigrants don't have the right to speak out on the job because they get fired."

Sitting alongside immigrants from Mexico, China, Sudan, the Philippines and elsewhere, Mr. González, 26, helped keep spirits from flagging, banging out Latin rhythms on a drum and bantering nonstop about soccer, salsa and discrimination.

"I can't wait until we get to Washington," he said. "I'm going to be screaming loud. I just want to make sure they listen to us."

The trip, by 900 riders on 18 buses, was inspired by the 1961 freedom rides that sought to integrate bus terminals in the South. Today's riders are pushing for legalizing the status of illegal immigrants, increasing visas for family reunification and stepping up protections for immigrant workers. Mr. González's bus originated in Los Angeles, and he boarded in Tucson after a rally at the Roman Catholic Cathedral that attracted 700 supporters.

"Immigrants do a lot of jobs that nobody else wants to do," he said. "They come here for one reason, to work. They make this place go. They help build America."

When he pushed to form a labor union to improve wages and conditions, he said, his employer dismissed him, suddenly telling him that his papers were not valid, even though his papers had long been accepted.

Mr. González now drives an ice cream truck. "I always heard about the American dream, and I'm still looking for it," he said.

He gestured to another passenger, Dhel Galwak Jourchol, a native of Sudan who immigrated to the United States to escape his country's civil war. "We have a lot in common," Mr. González said. "We both came to America alone, with no friends."

Mr. Jourchol fled Sudan for India, where he earned a law degree, and later the United States granted him refugee status. "Since my childhood, I never have seen peace at all," he said. "The war started in 1983, and we run from the bush to other places. I don't know where a lot of my family is. I don't know if my parents are alive."

Though he is protesting immigration policy, Mr. Jourchol, 32, is a cheerleader for America. "I love the freedom here," he said. "I want to take the system here, and someday establish it in my country. We really appreciate what America has done for us, and we will pay you back someday."

But Mr. Jourchol grumbled about discrimination against immigrants. He applied to work as a corrections officer but was rejected because he was not an American citizen. "I told them I'm qualified," he said. "I'm a law school graduate."

Guillermo Roacho, a diesel mechanic in Los Angeles, also complained about discrimination, saying employers exploited his fellow Mexican immigrants because many did not have legal status and faced deportation if they protested about anything.

"The Mexicans don't have nothing," Mr. Roacho said. "Without legalization, they have no rights."

He said he was so eager to join the bus ride that he told his boss he was going whether or not he was given time off.

Maggie Larson, a rider who immigrated from Malaysia, said she was blessed that she had never faced job discrimination. A housekeeper at the Royal Kona Resort in Hawaii, she said: "I work with people from China, the Philippines, Cambodia, Malaysia. We're very close. We take care of each other. I don't feel discrimination."

Ms. Larson, 41, who flew from Hawaii to Los Angeles to join the ride, said she wanted greater rights for all immigrants so they could share her happiness. She said she hesitated to join the caravan because it meant being away from her 6-year-old.

"Leaving my son for three weeks is a sacrifice, but other immigrants have not seen their families for 10 or 15 years," she said.

Few work harder than Grey Pichinte, a 23-year-old rider who immigrated from El Salvador. From 8 a.m. to 2 p.m. each day, Ms. Pichinte studies computer science at Rio Hondo Community College outside Los Angeles, and then from 5 p.m. until 1:30 a.m. she works as a janitor.

"Immigrants work more than anyone in this country," she said. "They work 16, 18 hours a day."

Tears filled her eyes as she described the riders' visit to Nogales, Ariz., where immigrants told of people who died in the desert seeking to enter the United States. Her parents crossed the desert to escape the violence and poverty in El Salvador, she said, eventually saving enough money to fly her to the United States.

"Immigrants deserve everything because of what they went through," she said. "They crossed the desert. They've made so many sacrifices to seek a better future. There are dumb people who don't see that."

Shirley Smith, a union organizer, was one of the few nonimmigrants on the bus. But she, too, had seen plenty of struggle. She was a high school senior in 1959 when whites in a Dallas suburb sought to prevent her and other blacks from attending a local school.

"They'd throw rocks at us, firecrackers, too," Ms. Smith said.

Ultimately, the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. flew to Texas to join that integration struggle. Today's ride, she said, was part of the same fight.

"Before this trip, I didn't realize that the Hispanic people were treated so bad," she said. "All they want is to live like other people. We're still fighting for people's rights. That's what Martin Luther King and Cesar Chavez died for."

Copyright 2003 The New York Times Company

http://www.nytimes.com |